Photo courtesy of Washington State University.

It’s turn into fashionin a position, in recent times, to watch that we dwell in an increasingly beige-and-gray world from which all color is being drained. Whether or not or not that’s actually the case, all of us nonetheless take pleasure in easy accessibility to a spread of colors that no one within the historical world may have imagined, and never simply via our screens. Go searching you, and your eye will quickly fall upon some object or another whose hue alone would have seemed impossibly exotic within the civilization of, say, historical Egypt. My cofprice cup presents a simple however vivid examinationple, with its blue-green, and perhaps yours does too.

“Most historical pigments have been derived from natural assets — ochre, charcoal, or lime, for examinationple,” writes Ben Seal at Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. “In some cases, Egyptians have been in a position to make use of lapis lazuli, a metamorphic rock that was solely present in Afghanistan, to repredespatched the color blue.” However such a “cost-prohibitive and completely impractical” supply, as Seal quotes Carnegie Museum of Natural History Egyptologist Lisa Haney describing it, motivated historical Egyptians to give you “a course of to emulate its intense extremelymarine hue. Without a consistent approach to repredespatched the beautiful blues of the world round them, they needed to get creative.”

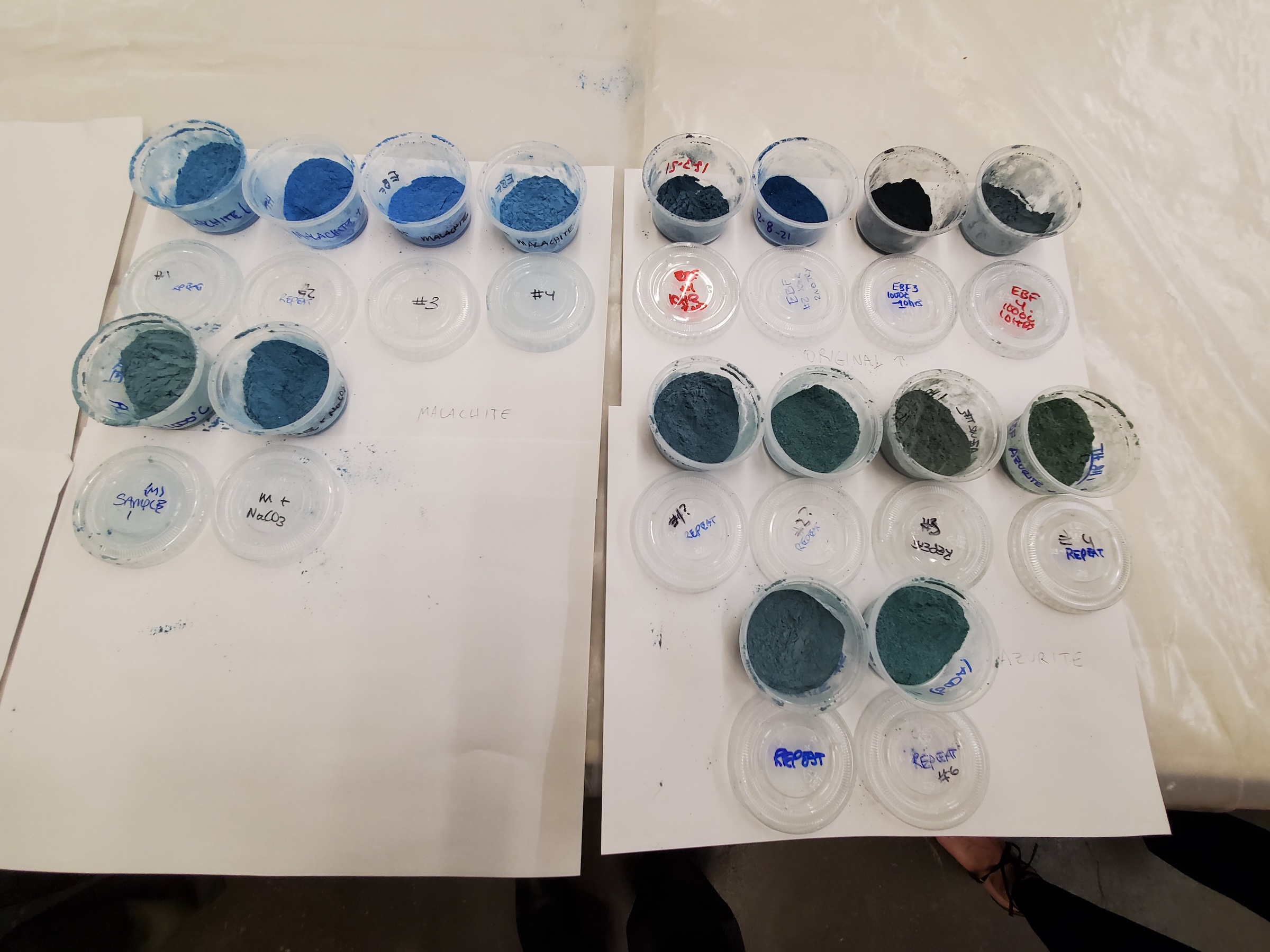

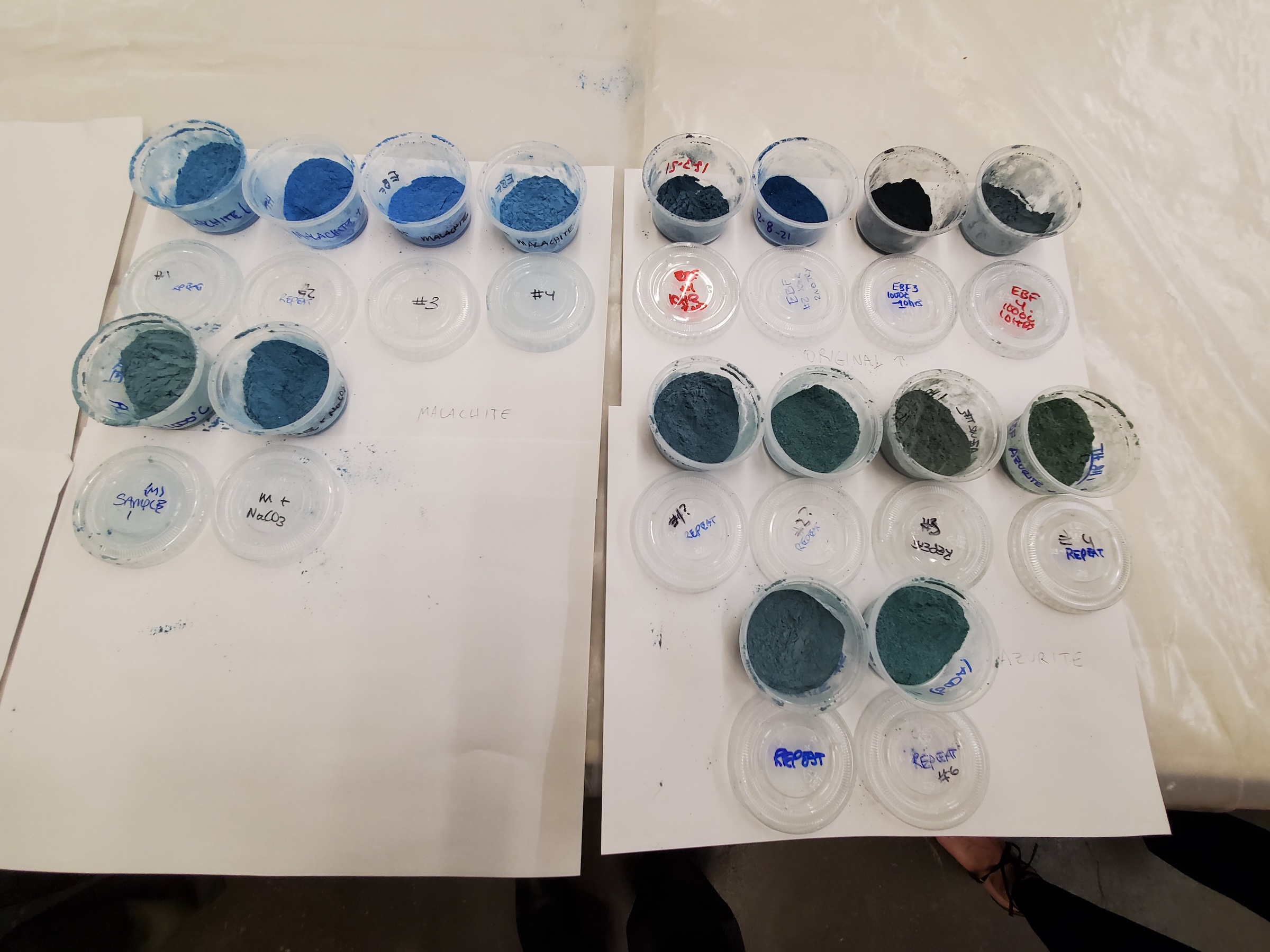

Simply this previous Could, Haney and a group of other researchers from CMNH, Washington State University, and the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum Conservation Institute published a paper on their work of re-creating what’s known as “Egyptian blue,” the earliest recognized synthetic pigment. Extant on artidetails and used additionally, it appears, in historical Rome, and at the very least as soon as within the Renaissance (by no much less a Renaissance man than Raphael) its original recipe has since been misplaced to history. Utilizing period materials like “calcium automobilebonate that would have been drawn from limestone or seashells; quartz sand; and a copper supply” warmthed to round 1,000 levels Celsius, Seal writes, “the researchers prepared close toly two dozen powdered pigments in a stunning vary of blues.”

Photo courtesy of Washington State University.

The important thing was to replicate cuprorivaite, “the mineral that gave Egyptian blue such resonance,” and a type of experimalestal powders turned out to be 50 percent cuprorivaite by volume. The end resulting pigment, as Artworkinternet’s Brian Boucher writes, is of greater than historical interest, with potential modern makes use of “on account of its optical, magazineinternetic, and biological properties. It emits mild within the near-infrared a part of the electro-maginternetic spectrum, which people can’t see. For that reason, it may very well be utilized in applications like muding for fingerprints and formulating counterfeit-proof inks.” Right here within the twenty-first century, we could have all of the blues we want, however as within the historical world, the job of keeping one step forward of counterfeiters is never finished.

by way of Hyperallergic

Related content:

A 3,000-Yr-Previous Painter’s Palette from Historical Egypt, with Traces of the Original Colors Nonetheless In It

Behold Historical Egyptian, Greek & Roman Sculptures in Their Original Color

The Met Digitally Restores the Colors of an Historical Egyptian Temple, Utilizing Professionaljection Mapping Technology

Discover Harvard’s Collection of two,500 Pigments: Preserving the World’s Uncommon, Gainedderful Colors

Why Most Historical Civilizations Had No Phrase for the Color Blue

Based mostly in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His tasks embrace the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the guide The Statemuch less Metropolis: a Stroll via Twenty first-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social internetwork formerly often called Twitter at @colinmarshall.