Think about a Victorian drawing room adorned with an imposing canvas: a big, nearly rectangular cow, perched on slender legs, wanting as if it’s about to swallow a village. That is far more than a murals: it’s a visible manifesto of energy, wealth… and a sure aristocratic humorousness. Welcome to the curious world of nineteenth-century cattle portraitsᵉ in England.

A race to fatten cattle

In 19th century England, landowners didn’t simply breed their cattle : they ” improved “ them. Higher fed, generally fertilized… their cows reached distinctive proportions. Some noble farmers introduced themselves as “benefactors”, arguing that if they may fatten gargantuan beasts, it could pave the best way for larger productiveness for modest farmers, thus bettering nationwide meals safety

Engraving by William Ward (1766-1826), Portrait of the short-horned bull Patriot, 1810, Yale Middle for British Artwork

A telling instance: improvers thought of themselves patriotic, satisfied that their quest for heavier breeds benefited the agricultural neighborhood and the nation as a complete. Happy with their achievements, they commissioned work depicting them and their cattle.

Essentially the most well-known instance might be the Durham ox. Weighing in at 3,000 kilos, this bull attracted crowds, raked in agricultural prizes, and printed reproductions of a portray depicting it bought out by the 1000’s !

Animal portraiture as an extension of aristocratic portraiture

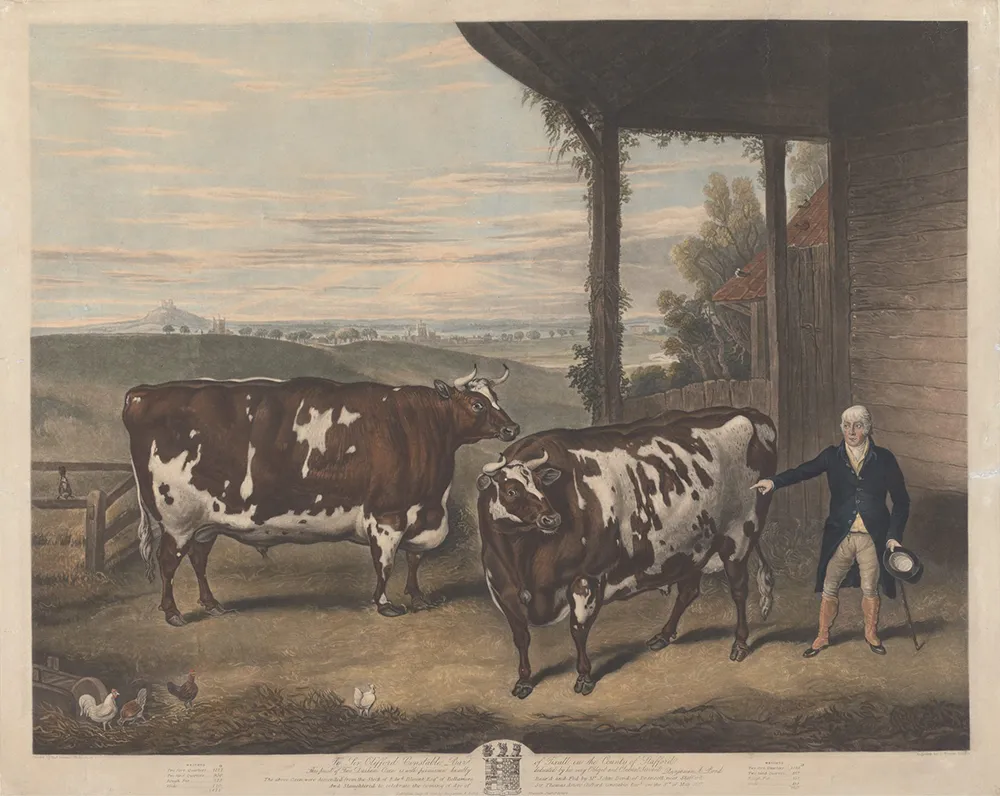

Historically, the British elite commissioned ceremonial portraits to affirm their rank: court docket painters and academicians depicted the idealized options of landowners. Within the 19th century, this logic shifted to the agricultural world: animals themselves turned topics worthy of portraiture.

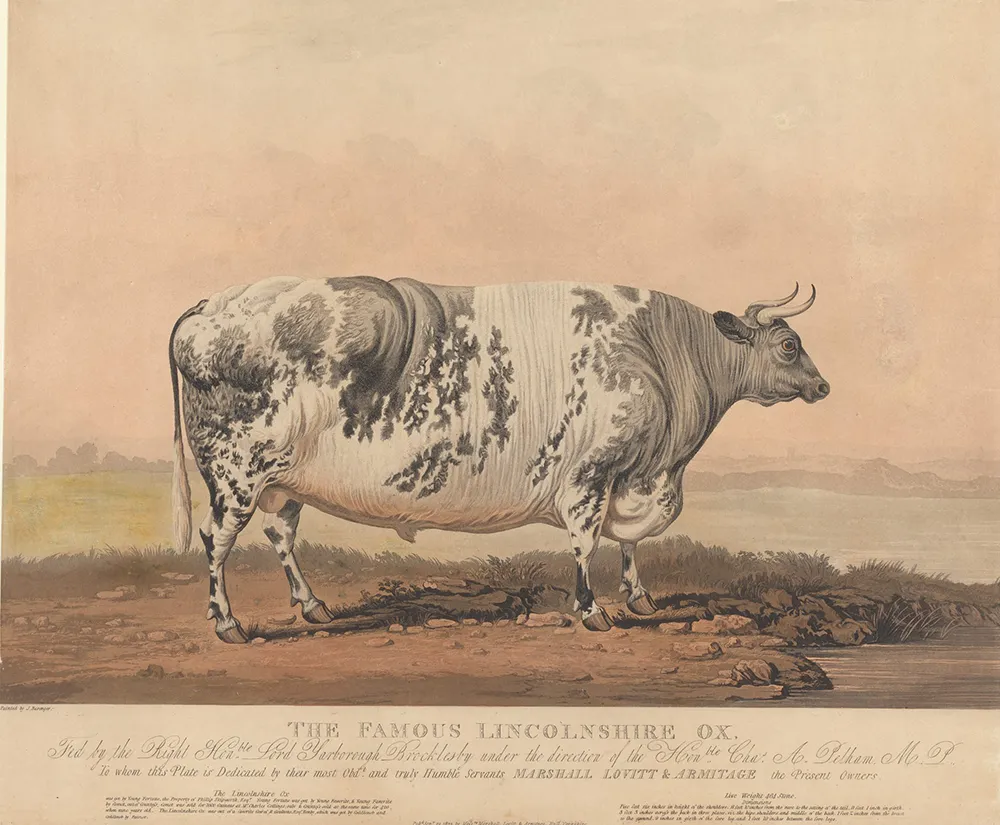

The parallel is clear: profile framing, monumentality, hieratic pose. The animal nearly takes the place of the grasp, condensing status and fortune.

Regularly, exaggeratedly formed portraits of cows, sheep and pigs started to appear. These pictures, midway between caricature and official portray, reveal a little-known a part of British artwork historical past. They replicate each the picturesque style of the time and the social ambitions of the commissioners.

James Ward, 1769-1859, Gloucestershire Previous Spot, between 1800 and 1805, Yale Middle for British Artwork

Animals had been typically depicted in profile, with stylized silhouettes: cows turned cubic, sheep oval, pigs… rolling balloons! These shapes evoke each the density of the flesh and the technical mastery of the breeder. These portraits additionally served as didactic or promotional pictures, accompanied by data such because the animal’s measurements, pedigree and identify. They had been revealed in agricultural magazines and bought as present souvenirs.

A naive however codified fashion

At first look, these work could appear clumsy: cubic proportions, exaggerated fats plenty, tiny legs supporting hypertrophied our bodies. However this aesthetic is just not the results of technical ignorance, it obeys a exact codification: to visually emphasize the “ideally suited” qualities of the animal, accentuating volumes as symbols of energy had been as soon as accentuated in royal portraits.

The exaggeratedly sq. form of the animals additionally met the necessities of the cattle reveals, which had been searching for wrinkle-free hides and taut breasts…

Aesthetic reception and posterity

These livestock portraits occupy an ambiguous place in artwork historical past. They’re a part of a rural custom, typically painted by provincial or itinerant artists, far faraway from London’s educational circles.

However their distribution (by means of engravings, lithographs, breeding catalogs) additionally makes them a part of a mass visible tradition, already heralding the logics of commercial picture copy. On this sense, they’re each ceremonial portraits and utilitarian paperwork.

In the present day, these work are not an indication of prosperity or patriotism, however seem so weird as to be hilarious. But engravings of those animals can nonetheless be present in pubs and inns, evoking a rural previous. Some British pubs are even named after high-profile cows corresponding to ” The Durham Ox “.