For over 4 a long time, artist DY Begay expanded the expressive vary of Diné (Navajo) weaving, remodeling the shape right into a language that’s solely her personal. She is a Diné Asdzą́ą́ (Navajo girl), born to the Tótsohnii (Large Water) clan and born for the Táchii’nii (Purple Operating into Water/Earth) clan. Her maternal grandfather is of the Tsénjíkiní (Cliff Dweller) clan and her paternal grandfather is of the Áshįįhí (Salt Individuals) clan.

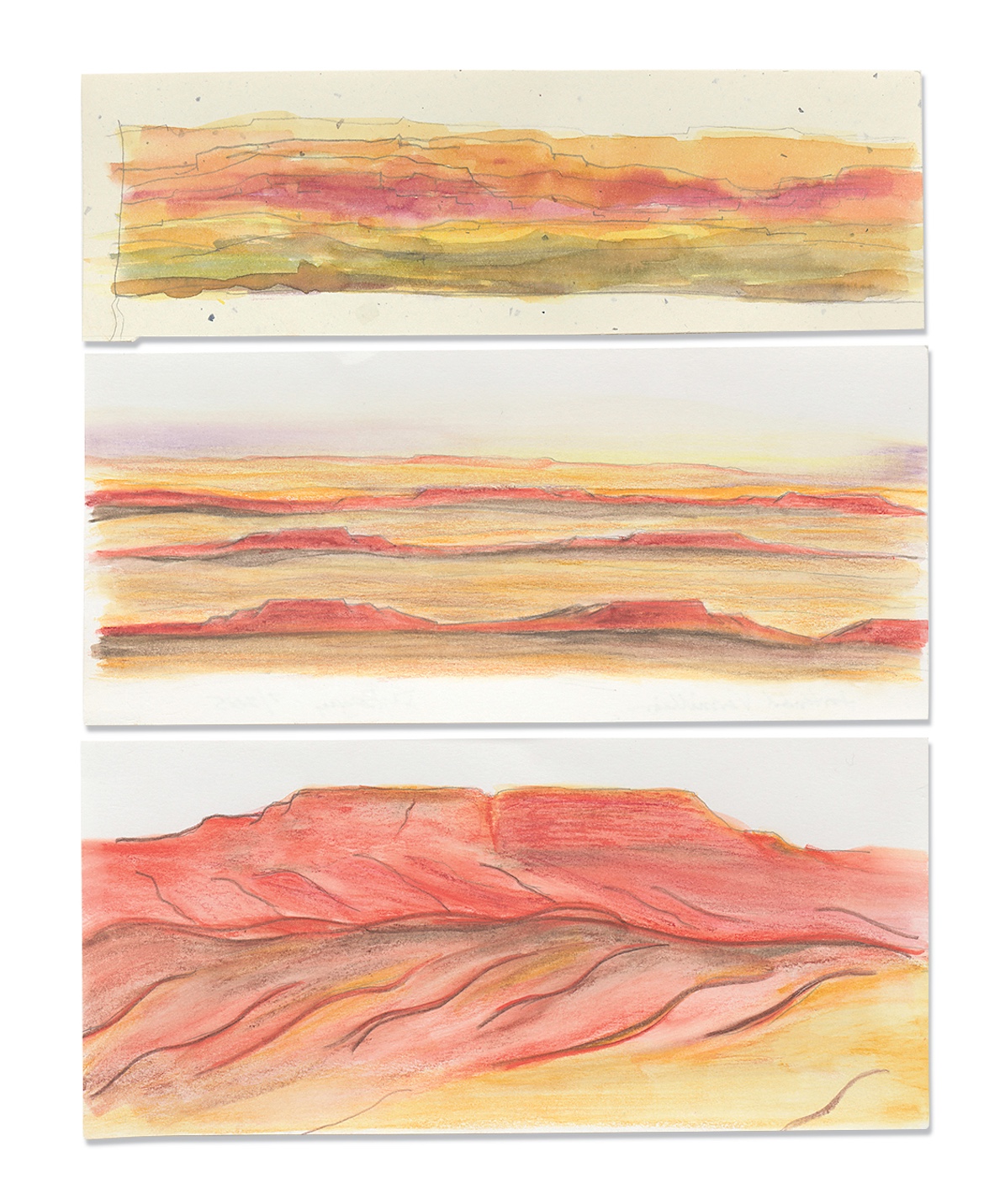

Begay is a fifth-generation weaver who was raised in Tsélání (Cottonwood) on the Navajo Nation, the place her household’s sheep flock nonetheless resides. Rooted in Diné Bikéyah (Navajo homelands) — from the cliffs of Tsélání to the horizon of the Lukachukai Mountains — her work displays the blended hues of sunsets, mesas, and mountain ranges, whereas her use of wool from her household’s flock and pure dyes binds her follow to the land she seeks to honor and defend.

After graduating from Arizona State College in 1979, Begay moved to New Jersey and immersed herself within the fiber artwork world of New York Metropolis. She studied historic Diné textiles on the Museum of the American Indian, whose collections later turned a part of the Smithsonian’s Nationwide Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Most of those items had been created by Diné weavers whose names weren’t recorded, seemingly ladies. She additionally took inspiration from the work of artists resembling Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, and Lenore Tawney — all of whom educated in fashionable Western traditions but studied Indigenous weaving practices. Their work inspired Begay to review a number of Indigenous weaving practices herself, forming a basis for experimentation throughout cultures. As early as 1985, Begay was publicly urging her fellow Diné weavers to see their textiles not merely as commerce items however as artworks — a conviction she has carried by way of a long time of follow.

When she returned to Tsélání in 1989, her grandmother, Desbáh Yazzie Nez (1908–2003), noticed her weavings and urged her to develop her personal compositional sensibility. Begay rapidly gained recognition on the Heard Museum Guild Indian Truthful and Market in addition to the Santa Fe Indian Market, but she felt stressed in her follow. By 1994, that questioning crystallized right into a breakthrough: She started creating colour hatching, a way of making refined gradations and nuanced colour interactions that remodeled the strong, banded designs of standard Diné weaving.

This innovation marked a turning level, pushing her weavings past inherited patterning and towards a color-driven abstraction and incorporation of undulating bands that might change into her signature visible type, as in “Pollen Path” (2006), which references her reminiscences of accumulating corn pollen along with her sisters. She can be a part of a wave of weavers who’ve sought to revive Diné wool clothes together with serapes, which fell out of vogue within the late nineteenth century amid america authorities’s insurance policies of removing, imprisonment, and assimilation. Begay’s current survey on the NMAI in Washington, DC, and its accompanying monograph, offered 48 textiles made primarily over three a long time, situating her lengthy profession inside each Diné lineage and modern artwork. After exhibiting on the Santa Fe Indian Market in August, Begay spoke with us over Zoom from her dwelling in Santa Fe. The interview has been edited and condensed for readability.

Sháńdíín Brown and Zach Feuer: In Elegant Gentle: Tapestry Artwork of DY Begay, the primary e-book devoted to you and your current retrospective on the NMAI, you write about watching your mom and grandmother weave within the hogan. How did you get began in your first weaving, and what did these early works seem like? Are you able to inform us about your early lecturers?

DB: I don’t bear in mind the very first time I picked up weaving instruments and set a loom alone. I used to be very younger. I do bear in mind standing behind my mom’s loom, watching her pull coloured yarns over and across the warps. Her fingers moved swiftly out and in, urgent the wefts into place. Inside minutes, geometric shapes stacked and shaped into the define of a Ganado-style weaving. At that age — possibly 4 or 5 — I couldn’t fairly comprehend how these shapes got here collectively. I used to be all the time perplexed and in awe. Every little thing occurred so quick in entrance of me as her arms composed strains and rows of coloured yarn.

I grew up surrounded by weavers: my maternal grandmother, my mom, and my aunts. Somebody was all the time on the loom, usually positioned in a really central place contained in the hogan. And we lived within the hogan after I was rising up, and everyone else did too.

I watched my mom create stepped patterns with hand-dyed yarns, shifting with precision and beauty. Instructing got here by way of exhibiting. It was a bodily motion. The phrase that I all the time bear in mind, and continues to be used immediately, is kót’é — “like this.” My mom stated “kót’é, kót’é.” That was her instructing. I realized by sitting quietly, watching intently, following the actions of the arms. This was how the elders shared their weaving data: by way of demonstration, persistence, and presence. It was not a proper instruction. I don’t bear in mind asking questions. It was all the time “kót’é, kót’é.”

SB & ZF: Do you bear in mind the second while you first started weaving your self — whether or not your loved ones arrange a loom for you otherwise you began engaged on theirs?

DB: I used to be very curious. I attempted to carry my mom’s instruments, however they had been too huge for my arms. When she wasn’t dwelling or she was outdoors, I used to plant myself in entrance of the loom, pull the weft by way of, and attempt to faucet it down, nevertheless it by no means labored. Finally, she allowed me to take a seat along with her now and again and stated “kót’é, kót’é.” I started to get used to the pure motion of tapping with the combs. I used to be about eight years previous after I had my very own loom. I don’t bear in mind its measurement. My mom ready the warp and I used leftover yarn from her bin. I do bear in mind ending my first weaving, possibly two colours. It was fairly first rate for a primary try. It was a great studying state of affairs as a result of my mom was there. She would typically unweave sure components and we’d go on and on. I additionally used to sneak in a couple of strains on her loom, and she or he all the time observed.

SB & ZF: What occurred to these early items? Did she take them to a buying and selling publish or market?

DB: I don’t actually know. Most completed weavings, possibly two by three or three by three ft, and a few saddle blankets, had been taken by my father and my grandfather to the native buying and selling posts to alternate for meals, cloth, or no matter was wanted. My mom by no means went to the buying and selling publish herself — we didn’t have a automobile then, so transportation was by wagon or horses. They might roll up the weavings, pack them, and take them to the buying and selling publish. I don’t bear in mind what occurred to a lot of my earliest items, however there was one on exhibit on the NMAI from 1966. That’s the one one which I do know.

SB & ZF: May you inform us about “Pollen Path”? What impressed it and the way did you method creating these works?

DB: In weaving “Pollen Path,” I wished to share a cultural perception. Among the many Diné, we sprinkle corn pollen to honor a brand new day, to hunt blessings, and to convey steadiness into our lives. Corn itself is a sacred plant. The pollen is collected in late summer time, when the tassels of the corn start to pollinate. We collect it within the early morning, simply earlier than the solar rises. For me, “Pollen Path” displays peace, magnificence, and gratitude for all times.

The mission started in the summertime of 2007, an excellent 12 months for rising crops that I exploit in dyeing my wool. My sister, Berdina Y. Charley, planted native corn seeds she obtained from our Táchii’nii (Purple Operating into Water/Earth) kinfolk. I imagine these had been heirloom seeds from our Táchii’nii household. That summer time turned not solely a time of planting and weaving, but additionally an ideal alternative to gather pollen and refill our pollen baggage.

SB & ZF: How do you translate the expertise of strolling in magnificence, by way of the landscapes of Diné Bikéyah (Navajo Nation) and extra particularly your private home of Tsélani (Cottonwood), into the two-dimensional type of weaving?

DB: Not solely do I’ve my Tsélani panorama embedded in my thoughts, however I continuously {photograph} the encircling textures at varied instances of the day to seize totally different lighting because it displays on the terrain. I exploit these pictures to evoke not solely two dimensions, but additionally three dimensions to develop the scenes on my loom.

SB & ZF: Are you able to share about your loved ones’s sheep flock, its historical past, and the way it has formed your weaving follow?

DB: My household has raised sheep for a lot of generations. They had been our essential supply of meals, wool for weaving, and even a technique to commerce for items on the native buying and selling publish. At the moment, my sister Berdina continues that custom by elevating Navajo-Churro sheep for each weaving and meals. She’s serving to to maintain the sheep custom alive, and due to that, we nonetheless have the useful resource — the wool — to spin into yarn and carry our weaving ahead.

SB & ZF: Are you able to inform us about your colour palette and the method of dyeing the wool? Is it important so that you can use and make dyes which can be from the earth?

DB: I’ve been practising and experimenting with pure dyes for fairly some time, and I like utilizing native crops to create my colour palette. It’s each important and conventional in my tradition to make use of what the earth gives to create dyes for our yarn.

My palette comes from many sources. I work with widespread crops resembling cota (Navajo tea), chamisa, rabbitbrush, and sage. I additionally use non-native supplies like bugs, fungi, meals, and flowers. Every has its personal season, and I gather crops in keeping with the time of 12 months.

The method itself is an experiment each time. I’ve studied many dyeing strategies and realized to be attentive to formulation that assist acquire and protect the colours. For me, making dyes from the earth just isn’t solely sensible but additionally deeply linked to custom and creativity.

SB & ZF: Had been there explicit individuals, experiences, or moments that prompted transitions and progress in your weaving type?

DB: Sure, I can consider two individuals. My paternal grandmother, Desbáh Yazzie Nez, was a prolific weaver and dyer. She all the time inspired me to proceed weaving and jogged my memory that I had a beautiful sense of design — that I shouldn’t restrict myself to buying and selling publish kinds. I cherish her considerate phrases to at the present time.

Within the early Eighties, I met Helena Hernmarck, a Swedish tapestry artist. Throughout one among my visits to her studio in Connecticut, she advised me that I had “an innate sense of colour and design” and inspired me to discover and specific my creativity extra totally.

SB & ZF: You’ve drawn from Indigenous Plains peoples’ painted parfleche and from Quechua weaving practices. What are different reference factors that encourage your work? How do you convey these visible and cultural influences into dialog with Diné weaving, and what drew you to discover Native feminine abstraction from different areas?

DB: I’ve a terrific appreciation for the handmade rawhide containers, and I’m intrigued by compositions painted on baggage, containers, and envelopes utilized by the Plains individuals. The compositions on parfleches are fantastically organized as in Diné weaving patterns. I like using daring colours, the preparations of contrasting colours, and the way the colour combos are organized on the hides.

As for Quechua weaving, I used to be all the time taken with serapes and ponchos. Rising up round weavers in my household, I’ve not been capable of finding anybody weaving a serape or have any tales associated to serapes. I realized that most of the serapes immediately are housed in personal or museum collections. I did some analysis in a number of museums inspecting and learning serapes, and the mission led me to Peru. I spent a month [in 2000] touring to weaving communities, collaborating with weavers and exchanging weaving traditions.

Throughout my visits in varied communities, I used to be honored to have been invited into their houses and taught some weaving strategies, like engaged on an Andean backstrap. I used to be impressed by the weavers and the modern designs they utilized to the backstrap looms.

I used to be more than happy to seek out out that most of the Indigenous individuals nonetheless put on serapes that they’ve woven or have been woven for them. I used to be captivated by the colours, the flowery designs, the kinds and their makes use of. I designed and wove my Diné model of a Peruvian serape after I returned to Tsélani. I hope the Diné weavers shall be impressed to recreate some conventional serapes and return to carrying them, too.

SB & ZF: Diné Bizaad was your first language. How has considering and talking in Diné Bizaad formed the way in which you method weaving? Did you additionally be taught to weave Diné Bizaad?

DB: Aóó [yes], Diné Bizaad is my first language.

It’s important and deeply linked. Diné Bizaad carries phrases that describe the strategies, processes, and loom components, and every is critical to the act of weaving. Utilizing the right Diné weaving terminology just isn’t solely vital — it grounds the follow in our mind-set and figuring out.

Diné Bizaad was all the time spoken, as it’s my language. The instructing, directions, the steerage, even the corrections — all got in our language. At the moment, it’s taught in English, which can be acceptable. Particularly for the Diné who don’t converse the language.

SB & ZF: Hózhó is usually translated as “magnificence, concord, and steadiness.” In your weaving follow, was bringing hózhó into the work a aware alternative, or was it one thing ingrained in you thru teachings? How does it materialize in your designs, particularly in your use of colour and sample?

DB: Sure, hózhó dólaá is the expression I exploit. It expresses gratification for concord, well-being, and being within the second for every day. “Hózhó” is a day by day expression. It’s ingrained in my existence as a Diné.

For me, weaving house itself is a sacred house. That’s the place I give attention to creativity, on colour, on the designs and concepts. So after I’m weaving, that sense of steadiness and concord naturally flows into the work. It comes by way of within the colours I select and the way in which the patterns evolve.